‘What’s in a name?’

– Shakespeare

When it comes to naming a book or a business, it’s an important step. You want something that represents the being of what is to be presented to the world. I thought I’d share this week the history of the naming of Right Ink On The Wall – partly because naming is storytelling in itself, and partly because the name has meaning to me. I’d like it to have meaning for you, too.

I wanted something that was punchy and played with words. Words and writing are so visually engaging – I could see inkwells and quills, pens and paper, books and shelves, typewriters and blotters, scribes and scripture, stone and chisels… graffiti and walls. I wanted to be a wordsmith, to tinker with words and their meanings, their spellings, their etymology. From the above, I bet you can guess many of the names that I searched, finding many taken. None of them were quite right anyway. They didn’t write well. And there it was, the writing on the wall. Suddenly, a whole host of wall imagery appeared – familiar walls and famous walls. And I thought about what walls can mean.

Walls can divide but they can also protect. Walls can be built but they can also be broken down. You can sit on one side of a wall or the other. You can hit a wall. You can overcome a wall. They can be associated with writer’s block and building blocks. They can be used for good or evil. And the best walls have strong foundations.

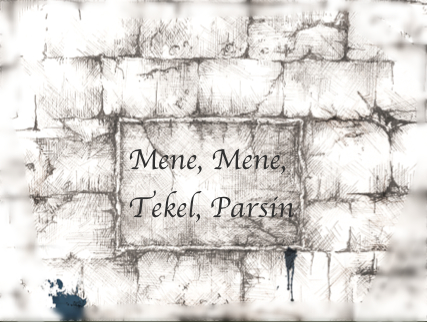

‘The writing on the wall’ is a tragic phrase whose history lies in scripture (Daniel 5). It’s a moral tale in which God plays with words, which are written on a wall by a disembodied hand. The sinful king, Belshazzar, has Daniel provide meaning where his wise men can only offer translation. The words are not a warning – they are a judgement. God has numbered the days of Belshazzar’s reign. He has been weighed on the scales and been found wanting. His kingdom will be divided.

I’d like to reclaim ‘the writing on the wall’ and create a shared understanding of my version, or vision, of The Wall. To me, The Wall is the infinite space where anything that has ever been written is recorded. It’s like the library of the world, or the facade of the world. And I want to invoke a feeling that The Wall is permanent. I suppose it’s a personification of history. The Wall is where you make your mark on the world and you want it to be right, as marks on The Wall, whether words or actions, go down in posterity.

The foundations of Right Ink On The Wall are not just about making the mark you write on the wall accurate but also leaving the right mark on the world. And encouraging people (much like myself not so long ago) who haven’t had the self-belief to act yet or make any mark at all, to actually make a move to write ink on the wall of the world, by whatever means. This message and mission can hark back to the implications of the doom-laden origins of ‘the writing on the wall’ and it recalls Steve Job’s third story in his Stamford address, in which he comments, ‘Remembering that I’ll be dead soon is the most important tool I’ve ever encountered to help me make the big choices in life.’ Yes, life is transient, we are temporary beings, i.e. life is short. So, we have the chance to pass out of the world with a whisper or to leave our mark on The Wall for others to read. And if we want to stamp ourselves on the world before we go, hopefully we want our mark to be morally good – leaving the right sort of ink on The Wall.

There is a fascinating history to the power of naming. It crops up time and again, from sacred texts to fairy tales. Why does Rumpelstiltskin’s name have such power? Why does Voldemort’s? There is consideration of the concept of ‘true names’ in philosophy, folklore and fantasy. A true name is considered powerful in that it expresses the true nature of a being. I hope that my name expresses the true nature of my business.

When it comes to business and branding and successful names, how have ‘Google’, ‘Skype’ and ‘Apple’ become so catchy? How have ‘Virgin’ and ‘Amazon’? There can be power in the naming of things, but I believe there is more power in the substance of things. The names that become important are not necessarily the ones we are bombarded with, through as much advertising as possible. Perhaps this works for some household names, but the names that have the most power are the names that have the most meaning, that are connected with ideas that connect with people.

So, the question isn’t: what’s your name? But, rather: who are you? As Shakespeare’s Juliet wonders, ‘What’s in a name?’